Opinion – Helena Theodoro Was a Pioneering Intellectual Who Promoted Profound Reflections

A few months ago, I published a series about orixás in this column. I was delighted by the positive reception: many people wrote to me, and others said they learned a lot. As a follower and scholar of Candomblé, I find it essential to reflect from other worldviews and meanings.

However, it is important to emphasize that this is nothing new. One author who has taught us greatly about this and was a pioneer in offering reflections in this area is Professor Helena Theodoro.

An internationally respected intellectual, she was the first Black woman to earn a PhD in philosophy in Brazil, in 1985. In an interview for the Anpof (National Association of Graduate Studies in Philosophy) website, Theodoro discussed this historic milestone.

“Writing my doctoral thesis about a ‘Candomblé terreiro’ and the thought of the German idealist school of Max Scheler was the result of the knowledge I learned at home, the African civilizational values, and how Europe used our technology to enrich itself and stand out in the world, as we brought technologies related to gold, precious stones, cotton, leather, copper, rice, etc., as well as spices to South America, especially Brazil. African thought built our homes, our food, and our customs, projecting our way of life to the world and making Rio de Janeiro the main reference center of Carnival, with our samba schools, street bands, and afoxés,” she said.

Theodoro is the author of several books that traverse different genres, such as Iansã: Rainha dos Ventos e da Tempestade (Iansã: Queen of the Winds and Storm), published in the Orixás Collection by Pallas, and the biography Martinho da Vila: Reflexos no Espelho (Martinho da Vila: Reflections in the Mirror), published by the same house. She is one of Brazil’s leading intellectuals to build bridges between philosophy, Afro-Brazilian religiosity, and popular culture.

Her pioneering spirit runs through many fronts of her career. In communication, she was a columnist for Rádio MEC, print media, and televised events. In theater, she wrote the trilogy Matriarcas (Matriarchs), with the plays Mãe de Santo (Mother of Saint), Mãe Baiana (Bahian Mother), and Mãe Preta (Black Mother), which have been staged in various institutions.

In an interview given to Amarello magazine, I was able to learn more about her personal and family history. The daughter of Black activists—the economist Jurandir Theodoro and interpreter Lea de Araújo Theodoro—she grew up in an environment that understood education as a tool of liberation.

Her parents had material means and political awareness—and passed both on as a legacy. She studied piano, ballet, and French. She attended samba gatherings, theaters, and lived among elders and African knowledge. She was always an excellent student everywhere she went.

A message that needs to be strongly conveyed to young people, especially those who experience discrimination, is that education and study open up paths and change lives. For brilliant people like Theodoro, these paths become gifts that are not individual but serve an entire community. It is like a crack opening in a cave or the first winds arriving from the east.

In a Brazilian philosophical field that is hegemonically male, white, and Eurocentric, only someone with such genius, courage, and ancestral blessing could defend a thesis comparing the philosophy of a Nagô terreiro—which, in itself, is a somewhat liberating proposition for a people so silenced throughout history, as much as it is scandalous to the Judeo-Christian epistemology that underpinned this exclusion—with the thought of a scholar aligned with the German idealist school.

As a Black woman, mother, and philosophy undergraduate at the Federal University of São Paulo, I did not have the opportunity to be her student. But meeting her outside the limits of academic parochialism was a gift. I became an enthusiastic reader of her work and presence.

At this year’s Portela parade, when the float with Milton Nascimento—a man of Oxalá, honored by the theme—entered the avenue, I was there on the float, on the right side, with other guests. And the first person I saw in the avenue was Theodoro, in the press box. I bowed to her from a distance. There too, with all the meanings that unite us—Oxalá, Carnival, the entrance, the first person, Exu—I felt that our paths had crossed.

What was born there turned into this tribute to open July, a month so politically important for Black women. May we all learn from Helena Theodoro to be like the windstorm—with thought, with courage, with axé. Your blessing. Thank you for so much.

Originally published in Folha de S. Paulo.

Related articles

July 13, 2025

Professor Djamila Ribeiro opens the Santa Catarina Congress on People Management

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

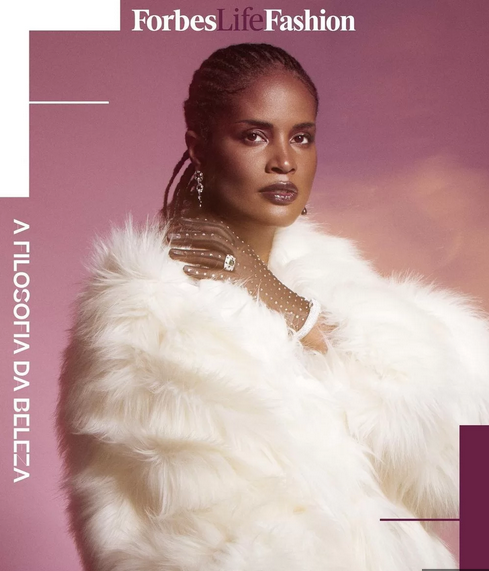

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life