A cinema that breaks silences

The film “Manas” explores the complex and troubling landscape of child sexual violence in Brazil

What happens when marginalized stories break the silence and take center stage? Manas, the film by Marianna Brennand, invites us to broaden our horizons and takes us by boat across a river journey with Marcielle—played by Jamilli Correa—through the disturbing, multifaceted, and complex landscape of child abuse in Brazil, especially on Marajó Island, in the state of Pará, where the film is set.

In recent years, the press and political discourse have increasingly addressed the abuses taking place on that island. Manas restores the region’s true colors—the purple of açaí, the green of its waters, the graphite of its mud—and, most importantly, its voices. It sparks a necessary conversation: sexual violence is not an exception, but rather a tautology. It repeats itself in the network, in homes, in trucks on the ferry, in party bathrooms. A routine of crimes masked by taboos—until cinema exposes it with the precision of those who know the weight of silence and the power of women’s solidarity.

It is already a reason for celebration to see a woman bring to the screen a film with such technical quality and aesthetic strength. Yet Manas goes further: its backbone is held up by women on multiple fronts—direction, production, and cast. This invites us to reflect on the transformative effects that arise when narratives created by historically marginalized groups—like us, women under a patriarchal structure—are made visible.

Brennand and her team masterfully construct a mosaic of eloquent silences. The camera does not need to show the violent act—it teaches us to read its traces in the diverted gazes of women, in interrupted gestures, in pauses louder than screams. The violence is present, but it does not dominate the scene with brutality. It insinuates itself—as it so often does in reality—between silences, rawness, and absences.

When violence does make itself explicit (and it does, in necessary scenes), it carries a weight that avoids sensationalism precisely because the film prepares the audience to understand it as part of a system, not as an “isolated incident.”

One character who struck me was Cinthia (played by Samira Eloá), a young Black girl in a supporting role as Marcielle’s friend. Notably, I struggled to find her name or even a photo during my research. There are no interviews or references to her role — and that, too, says a lot about lugar de fala, or place of speech.

Her character left a mark on me as I recognized in her the burden of a racist patriarchy. She invites reflection on the intersectionality that Black women like Zélia Amador de Deus—a Brazilian educator, living legend, and pride of Pará—have denounced for decades: she is sexualized before puberty, nurturing by nature, and strong by necessity.

As Professor Zélia Amador states in one of her works:

“Those from Marajó don’t escape. If you’re Black, you’ll learn early. Spaces are segregated. The big house belongs to the whites. The shack, to the Blacks. There’s no room for doubt.”

A careful look at these characters reveals how much a single accusation can cost; how economic inequality endured by women sustains the logic of child abuse, unwanted pregnancy, and unsafe abortion; but also, how the steadfast solidarity of many of us can carve paths for others.

These characters are joined by countless other women (and a few men) who, in “real life,” are doing everything they can—and much more—despite limited resources.

At the premiere in São Paulo, I met some of the real-life human rights defenders from the region who inspired the film—like Sister Maria Henriqueta, transformed into the character Aretha (played magnetically by Dira Paes), and police chief Rodrigo Amorim.

The casting is another triumph of the film, which marks the cinematic debut of Jamilli Correa, a young girl from Pará. Casting someone so young (she was 13 at the time of filming) in such a heavy role is a bold choice—and a spot-on one. Jamilli delivers a moving performance, full of contained fury and love for the women in her family.

Now, let’s be honest: if this film had been directed by a man, such a casting decision would be hailed as a stroke of genius. But when the direction is female, brilliance is naturalized. Wouldn’t you agree?

So, congratulations are in order for Marianna Brennand and the entire Manas team. The film, opening in theaters this week, presents cinema as a tool for repair, reflection, and social transformation.

This article was originally published in the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo.

Related articles

May 16, 2025

Professor Djamila Ribeiro Joins the Power Trip Summit 2025 in Salvador: Philosophy, Identity, and Social Transformation in Focus

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

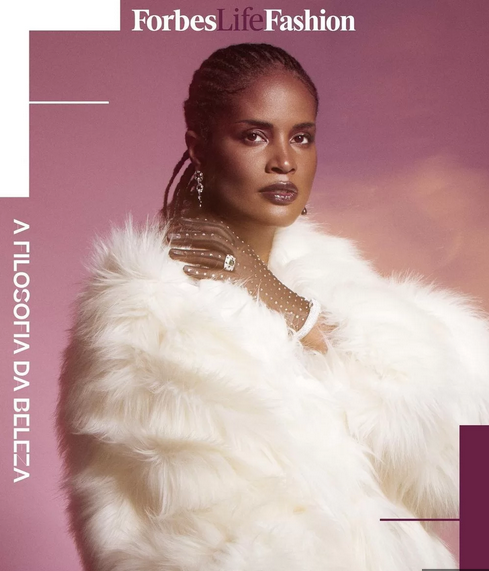

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life