At Flip, Professor Djamila Ribeiro dissects religious racism and points paths for the struggle: “Still much to do, but less”

Professor Djamila Ribeiro’s participation at Casa Folha, on July 31 during the International Literary Festival of Paraty (Flip), began with a provocation that set the tone for the debate: the censorship, last year, of her book Cartas para minha avó (Letters to My Grandmother) on a São Paulo state government platform aimed at teachers. The reason, revealed to moderator Anna Virgínia Balloussier by a source, was discomfort with references to Afro-Brazilian religions. The episode served as a starting point for the Brazilian philosopher to analyze the persistence of religious racism in Brazil.

Although the 1988 Constitution guarantees freedom of belief, Djamila reminded that persecution continues. She pointed to a constant duality in Brazilian history. “As Gilberto Gil says, the world worsens and improves at the same time. There is no linear path,” she said, stressing that even the slavery era was marked by rebellions, quilombos, and resistance.

One of the highlights of her analysis was the critique of what she called the “whitening” of African-based religious practices. When addressing the presence of white people in terreiros, Djamila explained that the problem arises when core practices are altered. She cited as an example terreiros that declare themselves practitioners of a “White Umbanda, Clean Umbanda,” positioning themselves as superior for not performing animal sacrifices. The risk, she pointed out, is “stripping these religions of their meaning and disconnecting them from their relationship with the community.”

This detachment from the roots leaves a social vacuum in the peripheries, which ends up being filled by neo-Pentecostal churches. Professor Djamila, however, warned against a simplistic view of the phenomenon. “We treat all these women as if they were ignorant, going against themselves,” she criticized, arguing that it is necessary to understand the complexity of the shelter these churches provide. “People need to learn to speak with instead of speaking to, and understand all this complexity.”

The discussion took on personal contours when Djamila shared her own journey, categorically stating: “religious racism drove me away from religion.” Initiated into Candomblé at the age of 8, she recalled the violence she experienced at school, where a classmate once tore off her turban. This experience expelled her from her own faith, leading her on a spiritual search that only brought her back to Candomblé at the age of 33.

As a former public school teacher, Djamila also discussed the challenges of implementing Law 10.639/2003. She reported that the biggest obstacle is the prejudice of many teachers who, when faced with themes such as capoeira, react by saying: “No, but that’s the devil’s work.”

In a scenario of constant struggle, the strategy, for her, involves self-care and ancestral wisdom. Using capoeira as a metaphor, Professor Djamila emphasized the importance of knowing when to attack and when to move gracefully. She recalled advice she received from older activists, who warned her about the need to preserve herself. On one occasion, when venting about how much still needed to be done, she heard a lesson she carries to this day: “There is still much to be done, but less because you are doing it.”

At the end, Djamila showed how Candomblé has become, for her, a liberating philosophy of life. Reflecting on motherhood, she highlighted that the archetypes of the orixás break with the logic of female guilt. “There is Nanã, who decided not to mother. […] So, a woman who does not want to mother in Candomblé has an orixá to whom she can direct her offerings.” For Djamila, this is the essence of a worldview that overcomes the exclusionary duality of Western thought. “The perspective of ‘or’ is very violent. ‘Either’ you are one thing ‘or’ another. In Candomblé, we have the perspective of ‘and,’ which comes from Exu. It is one thing ‘and’ another,” she concluded.

Professor Djamila’s presence in Paraty was a call for community organization against centuries of exclusion and for valuing ancestral traditions as a foundation for a more just future.

PHOTO: Mathilde Missioneiro/Folhapress

Content translated with the assistance of AI.

Related articles

July 30, 2025

Professor Djamila Ribeiro moved by meeting Vovó Cici in Salvador during Black Women’s July events

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

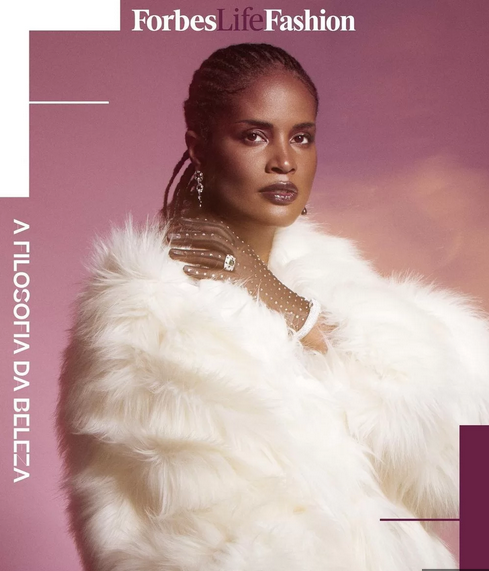

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life