Museums Are Sites of Struggle, Power, Memory, and Resistance

Exu was waiting for me at the British Museum, one of the world’s most important centers for cultural exchange.

On the last day of my stay in the United Kingdom, after an intense schedule of events promoting Where We Stand, the English edition of my book Lugar de Fala, I took an afternoon to visit the British Museum.

I was accompanied by Louise de Mello, head of the Santo Domingo Centre for Latin American Research, Sdcelar, and her Colombian colleague Santiago Valencia Parra. We went to the museum’s archive room, a restricted area not open to the public. And there, Exu was waiting for me.

Yes, Exu. The 1940s piece representing the orixá of communication, acquired by the British Museum, was the subject of an article I wrote in 2020, at the invitation of the museum itself—and the Research Center.

The text became part of the book Volver a Contar, published in both English and Spanish by the museum, where I reflected on the power and significance of this orixá. Standing before Exu, I asked for permission and for blessings: may he continue guiding Sdcelar’s path, one of the most important Latin-led museum justice initiatives currently underway in the Global North.

Sdcelar was created in 2019 with the mission of developing collaborative projects with Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities across Latin America and the Caribbean. Since then, the center has supported more than 30 initiatives in at least 15 countries.

The goal isn’t simply to “research” the museum’s Latin American collections—which hold more than 60,000 items—but to allow these collections to be interpreted through different perspectives, ranging from territorial struggles to epistemological frameworks. It’s a project grounded in the understanding that there’s no justice without self-representation.

Here, I need to make an important aside. I would really appreciate being spared the standard lecture about the colonial roots of European museums—as if we were naïve and didn’t know that these institutions, including the British Museum, were built on loot taken from African, Asian, and American kingdoms. Ignoring that would be just as naïve as ignoring that the institution is today one of the largest museum centers in the world, fostering decisive cultural exchanges across many countries.

Museums are not neutral. Like states, they are sites of struggle, of force, of memory, and of power. And they can become, if pushed, spaces for reconciliation, justice, and exchange. It’s precisely because I know this that the existence of centers like Sdcelar is so urgent.

Sdcelar’s work is necessary because it amplifies voices and redefines the very concept of a museum. With a lean but committed team—composed of Louise, Santiago, and Mexican scholar Clara Ruiz Álvarez—the center has facilitated artist residencies, exhibitions, and collaborative projects with Brazilian and Indigenous universities. One such project connects the National Museum at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, the Anthropology Museum at the Federal University of Goiás, and Iny-Karajá leaders from Bananal Island. In 2023, the center also hosted Wapichana Indigenous artist Gustavo Caboco, whose works will soon become part of the British Museum’s permanent exhibition.

These efforts, though modest in scale compared to the grandeur of the British institution, are revolutionary. They put into practice ideas of symbolic restitution, intercultural listening, and decolonization. When Ykaruni Nawa, a doctoral student at the National Museum, said that “self-demarcation is about applying pressure to change structures, and if museums need change, we need to self-demarcate them,” he captured with precision what Sdcelar has been doing: creating tension, from within, at the colonial foundations of European museology.

Today, I write this column with a mix of excitement and concern. Excitement for having witnessed firsthand the impact of a center working with such seriousness, sensitivity, and commitment to the peoples of the Global South. And concern because Sdcelar’s current funding will run out in September this year. We still don’t know if there will be a renewal.

Securing the continuity of this work is urgent. A center like this, housed in the world’s largest museum, is a rare window for fairer exchanges, international dialogue, and political presence for peoples historically silenced. Sdcelar needs institutional, governmental, and philanthropic support to continue existing.

That London afternoon, before boarding a flight to France, I said goodbye to Exu and thanked Louise for the guided visit. I left with the certainty that demanding reparations alone is not enough—we must also strengthen the initiatives already doing this essential work. And Exu is already there, standing tall, at the right crossroads, opening paths for this to happen.

Originally published in Folha de S. Paulo.

Content translated with the assistance of AI.

Related articles

June 19, 2025

Travel Log: Wits University – Johannesburg

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

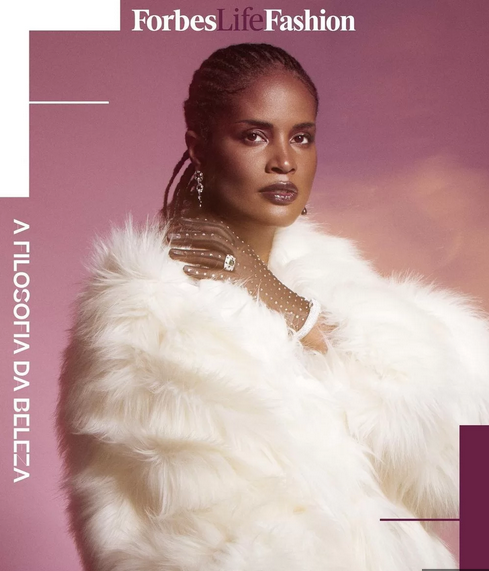

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life