Opinion – Violence Against a Kokama Woman Is Not Just an Isolated Individual Crime

I want you to stop and read carefully what I’m about to say. An Indigenous woman from the Kokama people was placed in a men’s cell with her newborn baby. There, in a public building of the state of Amazonas, this woman was raped for nine months by public security agents. Raped from the front and from behind, as she herself reported. Raped with her baby by her side, breastfeeding, still recovering from childbirth. Raped repeatedly, under threats and under the cloak of impunity. No police officer was investigated. No one was punished. The state of Amazonas offered her, as a response, compensation of R$50,000.

This woman now lives with physical aftereffects, deep psychological trauma, and a risk of suicide. She said, in her own words, that she was destroyed. And the State wants to offer R$50,000 as compensation. Fifty thousand reais.

Authorities must be questioned. Will the governor of Amazonas, Wilson Lima, remain silent again, as he did in the face of the brutal femicide of Julieta Hernández in 2024? Will silence in the face of brutality prevail? The banality of evil is institutionalized.

And the question remains: how can the Amazonas judiciary fail so glaringly in its oversight? The Public Defender’s Office and the Public Prosecutor’s Office must guarantee the inspection of all prison facilities in the state so that Brazilian law prohibiting shared cells between men and women is upheld. Who were the women imprisoned in the past by these same officers, and what did they endure?

This compensation proposed by the state government must be rejected outright, out of respect for the dignity of this woman, her child, and the entire Kokama people. It is time for the Brazilian judiciary to review the amounts it sets for compensation, especially when the claimants are from the poorest populations. It is important to emphasize that both mother and child suffered violence—this newborn was subjected to degrading conditions alongside his mother.

The first time I learned of this horror was recently, through a post by journalist Eliane Brum that opened my eyes. Eliane wrote:

“We need to stop and think hard about what kind of society allows something like this to happen not once—which would already be horrific—but for nine months, in a public building responsible for her safety, by security agents working for the State. How many people passed through there and did nothing? How many knew and remained silent? And how many now cover for these police officers?”

Eliane’s post led me to a report by Rubens Valente in Sumaúma Journalism, which rigorously and sensitively investigates the conditions at the Santo Antônio do Içá police station near the Colombian border—the place where the woman was held. The investigation documents, with forensic evidence and testimonies, the period of terror she endured. K., as she was called in the report, said the rapes began shortly after her arrest. A police officer entered the cell, lay down beside her, and violated her with her newborn baby by her side. From then on, night after night of abuse followed.

Commenting on the case, scholar Carla Akotirene offered a fundamental reflection. She reminded us that prison is a microstructure of the society of the enslaved. She stated that the technologies of oppression—patriarchy, racism, ethnocide, capitalism—intersect and materialize in prisons. The cell, therefore, is like a colonial reenactment. “The cell becomes a domestic environment,” says Carla, “where the man comes in and rapes, and when the woman tries to scream for help, she is punished for indiscipline.”

Carla also calls for federal authorities to intervene in the case, because it is not just an individual crime, but a systemic institutional failure that unites omissions, complicities, and normalization of violence against racialized bodies. “We need to demand what we call in governance ‘intersectorality and transversality of public policies.’ The Ministry of Human Rights, the Ministry of Women, and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples cannot work with their backs to one another.”

We cannot normalize barbarity. Speaking about this horror is also refusing to forget. It is to resist the attempt to cover up yet another tragedy with symbolic misery, political neglect, and institutionalized misogyny.

My condemnation of this horror and my solidarity with the woman and the entire Kokama people.

Originally published in Folha de S. Paulo.

Content translated with the assistance of AI.

Related articles

July 27, 2025

Opinion – In Candomblé Terreiros, Iyá Mi Are Not Conventional Orixás

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

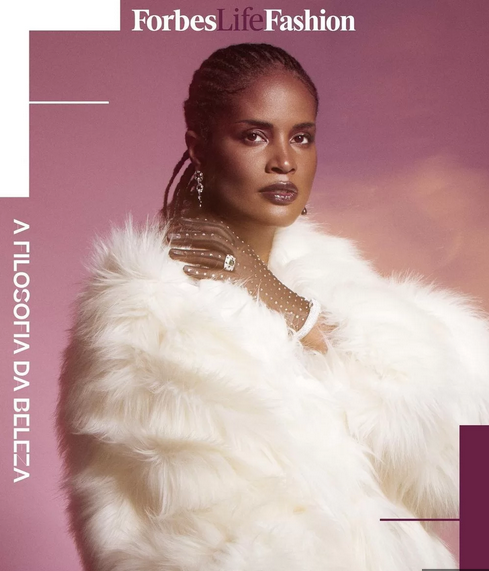

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life