Opinion: What gives the media the right to show a person being assaulted?

On July 26, in a luxury condominium in the Ponta Negra neighborhood of Natal, Brazil, Juliana, a 35-year-old librarian, was brutally attacked by her 29-year-old ex-boyfriend, a former player of the Brazilian national basketball team.

Inside an elevator, he delivered 61 punches to her face, leaving her bloodied and disfigured. She suffered multiple fractures to her jaw and face, required hospital care, and is now preparing for reconstructive facial surgery. The attacker was caught in the act and had his arrest converted into preventive detention. He will face charges of attempted femicide.

The case quickly gained widespread attention on social media. What struck me most was seeing many news outlets broadcasting the footage of the assault repeatedly, playing the sequence of punches in a loop while journalists narrated the violent scene. Even if the image was blurred or pixelated — and in some cases barely discernible — I find this deeply troubling.

Of course, the news had to be reported. But I believe it is crucial to question the supposed right these companies believe they have to broadcast someone being violently assaulted in this way, especially without their express consent.

For women — and especially for collectives of women — this repetition of images acts as a trigger for painful memories and traumatic experiences. It is essential to approach cases like this with care. And being careful does not mean downplaying or softening the severity of the issue — it means treating violence with the seriousness and responsibility it demands.

Even outlets that spared viewers the grotesque images fell into another trap: treating the 61 punches as an anomaly, something detached from the patriarchal society in which we live. This type of coverage fades quickly — tomorrow there will be another “isolated case” — and it detaches the story from the social structures that normalize violence against women in Brazil.

A view that truly upholds the dignity of women must connect this crime to all areas of society: culture, justice, sports, politics, economics, and even international relations.

If this man was a former player for the national basketball team, then investigative journalism shouldn’t just mention his sports career as if it were a mere curiosity. It should go further: what is the Brazilian Basketball Confederation doing in terms of training athletes around gender, masculinity, and violence prevention? What do those in charge have to say?

In my last column, I demanded a statement from the governor of Amazonas regarding the Indigenous woman subjected to nine months of sexual violence within the state prison system. He remained silent. In this case, however, Governor Fátima Bezerra spoke out immediately and expressed her solidarity.

Still, the crime occurred. So, with respect to the professionals working in the field, the media must follow up on the protection mechanisms that exist and investigate how — and if — they are actually accessible. It should assess their effectiveness and hold state-level executive, legislative, and judicial branches accountable in a collective effort to strengthen policies that prevent another woman from experiencing what Juliana did.

This would be possible if there were a genuine commitment to women’s lives. But how can we remain hopeful when Brazil breaks records for femicide and rape — as it did in 2024 — and these data fail to become front-page news?

The Annual Public Safety Yearbook exposed an ongoing massacre. Still, we continue to see violence treated as a “footnote.”

It is tragic — these are not footnotes, but record highs. And amid so many of them, and such a brutal case, questions abound. What were the previous federal government’s projects for women in the state? What was the budget? What about the current administration’s projects? When will the Casa da Mulher Brasileira (Brazilian Women’s Center) open in Natal? Why wasn’t it delivered earlier? What is the Ministry of Women’s budget today?

These questions fade away because, in the end, 61 punches depict a country where violence against women is structural and normalized — and where public policies for combating it are being dismantled and made generic.

A country that prefers sensationalism — and instead of confronting the reality — tries to put makeup on its raw, screaming truth. I deeply understand feminists who feel exhausted by it all.

Originally published in Folha de S. Paulo.

Content translated with the assistance of AI.

Related articles

August 10, 2025

In Her Birthday Month, Professor Djamila Ribeiro Is One of the Honorees at the 24th Ribeirão Preto International Book Fair

December 21, 2022

Djamila Ribeiro launches new website

December 21, 2022

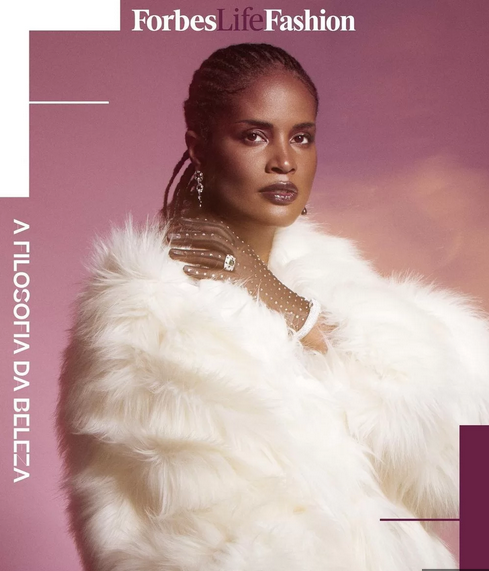

Djamila Ribeiro is on the cover of Forbes Life