Djamila Ribeiro brings Global South feminism to Italian magazine L’Espresso

Djamila Ribeiro’s presence in this week’s edition of the Italian magazine L’Espresso consolidates her standing as one of the most influential voices in contemporary critical thought. Named by the BBC as one of the 100 most influential women in the world, Djamila was interviewed by journalist Maurizio Di Fazio. The conversation addressed issues such as femicide, structural racism, inclusive language, and the role of peripheral feminisms in social transformation.

In the interview, the Brazilian philosopher stresses that the goal of Black feminism is not “equality on paper, but the radical transformation of society.” At a time when both Brazil and Italy face alarming rates of femicide, Djamila denounces this extreme form of violence as “a barbarity rooted in systems saturated with patriarchy and misogyny that continue to devalue women’s lives, especially those on the margins.”

The interview also marks the republication in Italy of the book Lugar de Fala (Il luogo della parola), with a preface by writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and a new introduction by philosopher Grada Kilomba. “Feminism is rooted in histories of collective solidarity,” Djamila emphasizes to the Italian magazine.

She also highlights the need to decolonize the Western gaze and to include, in the construction of narratives and theories, the voices of peoples who have been colonized: “We bring perspectives based on the lived experiences of those who have been silenced.” Reflecting on her teaching of “Feminisms from the Global South” at New York University, where she served as a visiting professor in 2024, the philosopher states that European and North American feminist paradigms cannot be exported without considering local realities.

Inclusive language emerges as one of the central tools of this transformative project. Djamila explains that it is not merely a matter of grammar, but a way of shaping how we see the world: “I prefer to use a vocabulary that includes and respects, even if it requires more effort, because I believe it is necessary to build bridges, not walls.”

The interview also addressed political issues. When asked about the presence of a woman at the head of the Italian government, the philosopher rejected the idea that representation automatically equals emancipation. “Emancipation is not only about being a woman in power, but about how that power is used to promote equity and justice.” She points out that Giorgia Meloni, by aligning herself with conservative discourses similar to those of Jair Bolsonaro, cannot represent any symbol of women’s liberation: “Claiming patriotism, attacking policies for vulnerable populations, and maintaining ties with militias is the opposite of feminism.”

With more than 1.3 million followers on social media and books published in several languages, Djamila Ribeiro continues to expand the horizons of Black feminism, forging a body of thought that combines theoretical sophistication with political practice.

Check out the interview below, translated into English using AI

Djamila Ribeiro, the Wave from the South – The Interview

Brazilian philosopher and activist, she gives voice to the new feminism and the antiracist struggle. “The goal is not to achieve equality on paper, but the radical transformation of society.”

Decolonizing the gaze, theory, and actions to confront the endless processes of whitening and masculinization of society. Brazilian, in her early forties, with a degree in philosophy and a master’s in political philosophy, Djamila Ribeiro is being mentioned more and more. A Black activist, best-selling author, and academic capable of captivating the most diverse audiences. Elegant and pop with her long braids, she is called upon by the United Nations and European universities; she holds a chair in “Feminisms from the South” at New York University; and the BBC included her in its list of the 100 most influential women in the world. And to think that she was the first in her family to complete her studies: her mother and grandmother had worked as maids in the homes of bourgeois—and white—families.

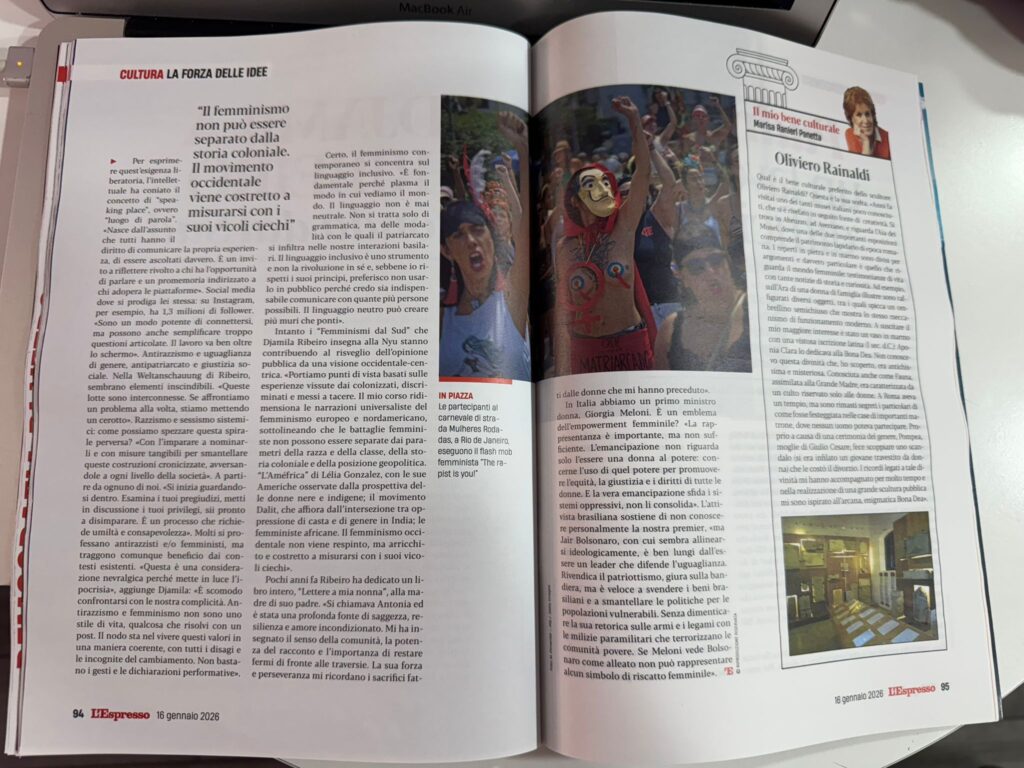

In Brazil, a country that abolished slavery in 1888, where every 23 minutes a Black person is murdered, and where “femicide is a barbarity rooted in systems saturated with patriarchy and misogyny that continue to devalue the lives of women, especially those on the margins,” the activist explains to L’Espresso. Books (published in Italy by Capovolte), lectures in symposiums and favelas, media appearances, and material support to a complex cause—this is how the new Latin American feminism for export spreads through her strong and clear voice. “The goal is not equality on paper, but a complete transformation of society where everyone—women and men—can live with dignity and freedom.”

Today, Ribeiro has become a symbol. “I see myself as part of a wave, rather than a single flag. Feminism is rooted in histories of collective solidarity.”

As in the case of Feminismos Plurais, a publishing series and physical space that supports women victims of domestic violence through psychological, legal, and social services. “We explore the various aspects of feminism. We wanted to break the curtains of silence, letting historically excluded voices guide the narrative. We no longer wanted to be relegated to footnotes in anthologies. We have already published 14 titles, written by Black women and men. For us, it’s not an unusual dialogue: if women are not a universal category, neither are men,” she affirms.

To express this liberating need, the intellectual coined the concept of “speaking place,” or lugar de fala. “It stems from the idea that everyone has the right to communicate their own experience, to truly be heard. It’s an invitation to reflect, directed at those who have the opportunity to speak, and a reminder to those who use platforms.”

She is very active on social media herself: on Instagram, for example, she has 1.3 million followers. “They are a powerful way to connect, but they can also oversimplify complex issues. The work goes far beyond the screen.”

Antiracism and gender equality, anti-patriarchy and social justice—in Ribeiro’s worldview, these are inseparable elements. “These struggles are interconnected. If we tackle one problem at a time, we’re just putting on a band-aid.”

Systemic racism and sexism: how can we break this perverse cycle? “By learning to name them, and by adopting tangible measures to dismantle these entrenched structures, opposing them at every level of society.”

Starting with each of us. “It begins with looking within. Examine your prejudices, question your privileges, be ready to unlearn. It’s a process that requires humility and awareness.”

Many claim to be antiracist and/or feminist, but still benefit from existing systems. “This is a key point because it reveals hypocrisy,” adds Djamila. “It’s uncomfortable to confront our own complicities. Antiracism and feminism are not lifestyles, something you solve with a post. The point is to live these values in a coherent way, with all the discomfort and uncertainty that change brings. Performative gestures and declarations are not enough.”

Certainly, contemporary feminism focuses on inclusive language. “It’s essential because it shapes the way we see the world. Language is never neutral. It’s not just about grammar, but about the ways patriarchy infiltrates our basic interactions. Inclusive language is a tool, not the revolution itself—and although I respect its principles, I prefer not to use it in public because I believe it’s essential to communicate with as many people as possible. Neutral language can build more walls than bridges.”

Meanwhile, the “Feminisms from the South” that Djamila Ribeiro teaches at NYU are helping awaken public opinion from a Western-centric view. “We bring perspectives based on the lived experiences of those who were colonized, discriminated against, and silenced. My course deconstructs the universalist narratives of European and North American feminism, highlighting that feminist struggles cannot be separated from race, class, colonial history, and geopolitical position. Lélia Gonzalez’s ‘Améfrica,’ with her Americas seen from the perspective of Black and Indigenous women; the Dalit movement, which emerges from the intersection of caste and gender oppression in India; African feminists. Western feminism is not rejected, but enriched—and forced to confront its blind spots.”

A few years ago, Ribeiro dedicated an entire book—Letters to My Grandmother—to her paternal grandmother. “Her name was Antonia, and she was a deep source of wisdom, resilience, and unconditional love. She taught me the sense of community, the power of storytelling, and the importance of remaining firm in the face of adversity. Her strength and perseverance remind me of the sacrifices made by the women who came before me.”

In Italy, we have a female prime minister, Giorgia Meloni. Is she a symbol of female empowerment? “Representation is important, but not enough. Emancipation is not just about being a woman in power: it’s about how that power is used to promote equity, justice, and the rights of all women. True emancipation challenges oppressive systems—it does not reinforce them.”

The Brazilian activist says she doesn’t know the Italian prime minister personally, “but Jair Bolsonaro, with whom she seems ideologically aligned, is far from being a leader who defends equality. He claims patriotism, swears by the flag, but is quick to sell off Brazil’s assets and dismantle policies for vulnerable populations. Not to mention his rhetoric on weapons and his ties to paramilitary militias that terrorize poor communities. If Meloni sees Bolsonaro as an ally, she cannot represent any symbol of female emancipation.”

Related articles

January 23, 2026

Thulane admitted to the University of São Paulo

January 16, 2026

Digital Expansion: Djamila Ribeiro Launches LinkedIn Profile and Broadens Professional Dialogue

January 10, 2026

“Mãe Ana was a woman who opened many paths”: Djamila Ribeiro pays tribute to Ialorixá Mãe Ana de Ogum